Filipino Art Songs: The Evolution of the Kundiman Genre and its Role in Filipino Identity in the Midst of Colonization

Why Filipino Art Songs:

As a first-generation immigrant, I felt the need and responsibility to represent my heritage in all things positive. Personally, I somehow grew up paralleling the idea of being exotic and unsophisticated. Like I always had something to prove. I had a wrong notion that “classical” music — as defined by Western classical music was “sophisticated” — that anything outside the box of Western classical music was simply distasteful or unacceptable. You can read about the process, on my actual paper under this introduction.

Are Filipino Art Songs the same as Ruben Tagalog’s renditions of kundiman?

A lot of Filipinos know Ruben Tagalog singing kundiman (yes that’s his last name): his suave voice and the nylon guitar in the background…

“Oh, Ilaw. Sa gabing, malamig…”

It is a kundiman, but can it be an art song?

What is an art song? It's a song usually based upon a poem or text, often accompanied by piano and other instruments. It is performed in a recital setting, or some sort of social event. When we think of art song, we think the German lied or the French melodie.

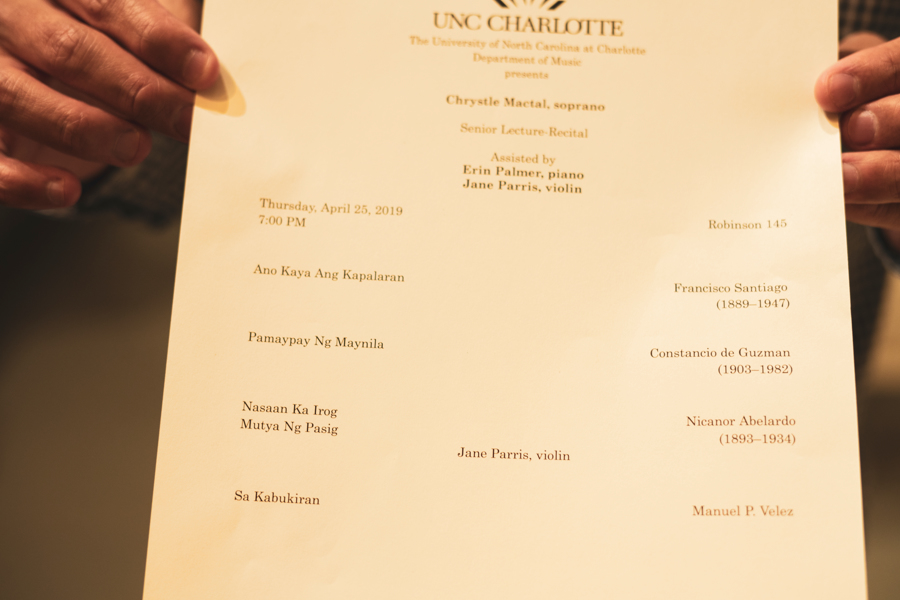

Here are a few pictures from the Lecture Recital…

Written by Chrystle Mactal

April 2019

Introduction: I was born in Saipan, Northern Mariana Islands as an American citizen, but I consider myself Filipino and raised in the Philippines even if I was there only until I was 7. With some sacrifices to be made, my family moved to the States just like anyone else: for better opportunity. Thanks to the guidance of my parents, the Filipino culture is very much a part of me even if I lived here most of my life. Into my sophomore year here at the music department, Dr. Deeter challenged me to look into Filipino classical music. Honestly, I did not know there was such a thing. I only knew of some folk songs passed down to me from my grandmother or of the tinikling dance. I had a terribly wrong notion that my culture could never own something as “sophisticated” as classical music. Why I thought that way while I proclaim to be a proud Filipino, I’m also interested in discovering myself. There is definitely a bridge with this notion and the diaspora of Filipinos from their homeland. I found myself ignorant of my own heritage. Nevertheless, I decided to take this rare opportunity to find my identity in music as a Filipino-American.

Acknowledgements: I would like to acknowledge the people who have helped me during this journey of figuring out what this music is. My professors: Dr. Alissa Walters Deeter, who served as the foundation of my studies in classical voice; Dr. Grymes, the most encouraging and informative to help me with this paper; Dr. Dupont, who graciously has taken time to be a part of my project committee; Dr. Priwan Nangongkham for his hospitality, for allowing me to perform these art songs at Kent State University and for meeting Southeast Asian Music Scholar Dr. Terry Miller; Professor Christina Pier, who has helped me discover my role in Filipino art songs through connecting the techniques I learn during lessons and taking it beyond; Erin Palmer, who has bravely made this music come alive and challenged me to step out of my bubble and take ownership in this music; and Jane Parris, the first fellow classmate and friend to collaborate with me. I’d like to mention my other professors that I’ve come across to during my time here, who have taught me so much more than just reading music. I especially would like to thank my friends and my family, who have supported me in every way possible in these past couple of years. It’s because of you that I am able to do what I am passionate about.

The Dilemma in Defining what is Uniquely Filipino

During the introduction of the potential thesis of this project, Dr. Grymes challenged me to explain what makes Filipino music distinct from Spanish music. Is Filipino music just Spanish music sung in the Tagalog language? Indeed, the three hundred years of imperialist Spanish rule dominated Filipino culture. This brings the dilemma in defining what is uniquely Filipino. But, what makes Filipino music unique is the mixing of existing traditions with the new Hispanic ones.. Journalist Carmen Guerrero Nakpil said this in 1997, “This very Westernization of Filipino tastes is responsible for the modern excellence and sophistication of Filipino music performers. All other peoples in Asia and the Pacific have only five notes in their ears. We Filipinos, thanks to the assiduous friars who made choirboys and musicians out of the Filipinos, carry seven notes, the do-re-mi of the European octave and have the distinct advantage of familiarity with the inventory, repertoire, and musical codes of Western music” (Castro, 2011, pg. 23).

“This very Westernization of Filipino tastes is responsible for the modern excellence and sophistication of Filipino music performers. All other peoples in Asia and the Pacific have only five notes in their ears. We Filipinos, thanks to the assiduous friars who made choirboys and musicians out of the Filipinos, carry seven notes, the do-re-mi of the European octave and have the distinct advantage of familiarity with the inventory, repertoire, and musical codes of Western music”

The Spanish Conquest of the Philippines

On the first sentence of the national anthem “Lupang Hinirang,” composed in 1898 by Julian Felipe, the Philippines is referred to as “Perlas ng Silanganan”--“the Pearl of the Orient Sea.” Known for its paradise-like beaches, the Philippines is an archipelago of more than 7,000 islands that consists of 77 provinces and a division of 15 different regions. The separation of land by water resulted in varying ethnic groups and a great division of languages and culture. Although it is only the size of the state of Arizona, this country has a total of 100 or more dialects that are actively being used today. My family, for example, comes from the province of Pampanga and speaks Kapampangan. My husband comes from Bulacan, and they speak Tagalog.

There is not much recorded history of the Philippines prior to the arrival of the Spaniards, but according to Castro, “there was a core population of racially similar people throughout the Philippines and Southeast Asia”. Three large groups of early inhabitants included the Negritos, also called the Aetas, who originally migrated from Southeast Asia, the Indonesians, the Malays, and the Chinese. Several foreign visitors like the Chinese were involved in trade and intermarriage and the earliest recorded time Chinese merchants visited the Philippines to trade was as early as 982 A.D. (Bañas, 1970). Also referred to the “Italy of the Orient”, the Philippines could arguably be the most westernized country in Southeast Asia. The first arrival of the Spaniards was recorded in 1521. Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, who had just conquered Mexico, made the same trip to the archipelago, and the Spaniards successfully conquered Cebu, then, Manila in 1571. Over the next three-hundred years as a Spanish colony, the Philippines, adopted a great deal of Hispanic culture. The Spanish language instilled in Tagalog, the surnames of the people, the cuisine, the Catholic religion, and the way the people dressed are just a few examples of how much Spanish culture influenced what Filipino culture is today.

Catholicism’s Effect on Filipino Sacred and Secular Music

Catholicism was the main driving force of the quick societal and cultural change in the Philippines. The Spanish Crown’s main objective through colonization was for an increase in monetary assets, but it was also very much interested in converting the Filipinos to Christianity. Though the initial intention of economic growth failed, the Christianization of the Filipinos was a success, and music became a significant platform for communication between the Spanish settlers and the native Filipinos. Prior to the arrival of the Spaniards, Antonio Pigafetta, a scholar who travelled with Magellan, documented his observations of the indigenous musical traditions. Pigafetta described traditions that included vocal music and instrumental music of gongs, drums, flutes, zithers, lutes, clappers, and buzzers. Vocal music genres consisted of epic poems, festive songs for special occasions, and work-songs sung during harvest time (Canave-Dioquinio, 2011). Such traditions changed quickly due to the Western musical influence that came along with Christianization. Missionary priest Juan de Santa Marta of Zaragoza, Spain, organized a choir of 400 boys. The primary school for boys, called primeras escuelas-de ninos, involved not only literacy and arithmetic, but musical instruction as well. Taught by followers of the Franciscan, Augustinian, and Jesuit orders, the boys learned about Gregorian chant (canto llano), polyphony (canto de organo), and hymns (salves). Liturgical music rapidly spread and created a uniquely Filipino repertoire that represented a fusion of their indigenous past with their Spanish culture. Three and some centuries of Spanish colonization, has generated a variety of repertoires and genres among the Filipino Christian population. Surprisingly enough, the Catholic movement would indirectly influence the characteristics of Filipino secular music, as well.

Western Influence in Filipino Secular Music

Having practiced liturgical music for centuries, the Filipinos now sought entertainment in music. Foreign dances from Mexico, Spain, and other European countries were being danced at balls or parties (Dioquino, 2011). “The favorite dances were the fandango, the jota, and the balitao. The more educated prefer the waltz, the polka, the habanera, the rigodon, and the lanceros” (Dioquino, 2011, p. 126). In addition to the exposure of dances from Western countries, opera brought a great interest among the Filipinos. It became common for “educated elite” musicians called ilustrados to gather for social gatherings in what they call tertulias, to perform operas of Rossini or Verdi (Dioquino, 2011). These popular social activities that involved these styles influenced the characteristics of Filipino art songs.

Filipinization and the Role of Music in the Early Twentieth-Century Philippines

“Filipinization —- the process of making culture more Filipino in order to counter the effects of colonialism and/or further a stronger sense of localized identity.”

Christi-Anne Castro Ethnomusicology professor of the University of Michigan - author of Musical Renderings of the Philippine Nation

Christi-Anne Castro’s book Musical Renderings of the Philippine Nation discusses an important idea. Castro discusses the journey of the Filipino cultural identity in which composers created certain types of music as an act of defiance against colonial oppression. Castro describes this as an example of “Filipinization” which is “the process of making culture more Filipino in order to counter the effects of colonialism and/or further a stronger sense of localized identity” (Castro, 2011, pg. 33). While still adhering to Western musical idioms, composers found a way to define Filipino music as a hybridity of pre-colonial and post-colonial music. Antonio Molina, composer and a nationalist advocate University of the Philippines urged the need for a creation of music that they could define as Filipino: He says,“The new tempo of Philippine life demands that our music take a new direction… It must reflect actual happenings and national events; for music is, in a way, a historical and social document.” (Banas, 1970, p. 7). This demand for national identity could have led composers to limit their musical language to that which was learned prior to the Spanish arrival. Instead of ignoring the reality that Filipino musicians had already been fully westernized for in many centuries, the nationalist composers used Western musical idioms to amplify or create genres that would help define Filipino music. This deliberate choice was due to their desire for progress and modernism. In the sense of seeing patriotic compositions as a tool of defiance against colonialism, prominent Filipino composers like Francisco Santiago, Nicanor Abelardo, and Antonio Molina could easily be revered in the same way Filipino national heroes like Jose Rizal, Andres Bonifacio, or Emilio Aguinaldo are respected. The composers created the kundiman. The kundiman is the art song of the Philippines with folk-music influence set to texts. But most people refer to them as classical love songs. The early kundiman were compositions of songs that involved the “affection and devotion” to the Motherland and were called kundiman ng himagsikan (revolutionary kundiman). Therefore, the theme of affection towards their country could easily be confused with a love situation with a real person.

Dr. Francisco Santiago, composer. Also known as the“Father of the Kundiman” b. 1889 - d. 1947.

Oppression or Love? “Ano Kaya Ang Kapalaran” by Francisco Santiago

Is it talking about oppression or love? “Ano Kaya Ang Kapalaran,” which translates to “What Fate Lies Ahead,” is a perfect example of a kundiman that people over the years have mistakenly sung as a love song. This song was composed in 1938 by Dr. Francisco Santiago, the “Father of Kundiman” or according to Castro, the “Father of Philippine Nationalism in Music.” Aside from being trained in the Philippines, he received his Masters and Doctoral degrees in the Chicago Musical College (now part of Roosevelt University). Santiago was also one of the first Filipino professors to teach in the University of Philippines. Santiago was a major proponent of Filipinization as well. He conducted research on folk songs from different provinces, and was able to notate and harmonize them. Personally, I discovered that the only folk song I know in my provincial dialect Kapampangan, “Atin cu pung sing-sing”, “I Once Had a Dear Ring”, was actually harmonized by Santiago.

The first time I came across this “Ano Kaya ang Kapalaran”, I was confused if I am to sing both the Tagalog and Spanish text because repeat signs of the sections are missing. Though the texts do not translate equally, both carry the same idea that “Happiness is not necessarily about finding one’s beloved but being free to sing his or own melody” (Anderson, 2015, p.56). In this case, the freedom in singing in their Tagalog language: “walang kasing tamis gaya ng umawit ng sariling himig. Bawat taginting ang wika’y pagibig.”, “there is nothing more pleasant than to sing one’s own melody. With every sound, the language is love”. The Spanish text explains further, “It is more than the song of the heart, it is the Philippine lyre”. The song quickly changes it’s mood in the second section, which goes into the parallel major. The Tagalog text of this section ends a bit pessimistic, “Expect not fortune, you will receive bitterness”. But, the Spanish text of the same section ends a bit more hopeful, “And if the pain is so great, the song sings the smile of the wounded heart…what you will achieve if you have hope. Happy you will be!”. Thought the Tagalog text satirically plays along the melody of this piece, the Spanish text amplifies the hopeful melody.

Highlighted is the Spanish text

“Pamaypay Ng Maynila” a Balitaw by Constancio de Guzman

As mentioned before, the kundiman is inspired by folk music.“Pamaypay Ng Maynila” “the Fan of Manila” was composed by Constancio De Guzman during the American colonial period of the Philippines (late 1800s to 1940s). His most famous song is“Maalaala Mo Kaya” which is the theme song of the iconic Filipino drama anthology that’s been running since 1991. He is also known for composing the kundiman, “Bayan Ko”, which translates to “My Country”.

Though de Guzman was popular for nationalistic kundiman songs, “Pamaypay Ng Maynila” which means “Fan of Manila” is a great example of a kundiman that is inspired by the balitaw. The balitaw is a musical debate in form of courtship that derived from the “pre-Spanish games of wit called duplo and karagatan” (Dioquino, 1998, p. 851). Like other kundimans, this song is in ¾ time to imitate the waltz-like dance, and starts off in the minor key. This piece is separated into three sections. The first section, the singer introduces her fan. The second section, she describes the way she uses her fan. The last part, modulates to the parallel major key and the singer continues to explain her love of the fan. If you are in the Philippines, you will notice that every woman will carry a fan around with her. “The fan, used by seemingly demure ladies, becomes symbolic in the wide array of attitudes and emotions it could convey – from shyness and coyness to outright flirtatious expressions of love, depending on the gestures used when fanning” (Filipinas Heritage Library, 2018).

The Kundiman vs. The Harana

In keeping the romantic essence true to its Filipino-Spanish culture, the genres are generally folk songs that are sung to court someone, or pangliligaw. For example, the harana, which means to serenade, is an old custom with which many modern Filipinos are still familiar with. All thanks to the novelty song released in 1997 amusingly called, “Harana” by Parokya ni Edgar, popular music fans are aware of the courting custom. The harana is rather a simple concept of a man, along with his “wingmen,” serenading a girl by her window, usually with the typical nosy audience awaiting the next subject of tomorrow’s gossip. The harana is a descendant of the Spanish serenata, or “serenade.” “Unlike opera, in a serenata there is no plot. Dioquino says that the structure of these songs follow the Tagalog poetry (plosa) but the music follows the Western music idiom in its I-IV-V chord progression, and often accompanied by guitar (Dioquino, 1998). Though the custom is losing its popularity, “Aking Bituin” or better known as “Oh, Ilaw” popularized by Ruben Tagalog, is one of the most famous haranas still sung today. Sometimes, it is sung in respect to the courting tradition, or one may amusingly hear it when driving by a typical Filipino karaoke bar.

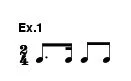

Danza rhythmic ostinato derived from the habanera or tango

Florante Aguilar, a Filipino multi-instrumentalist from San Diego whose expertise is in Filipino folk and art songs, wrote a blog about the differences in the kundiman and harana. First and foremost, the kundiman is in the triple meter that starts in a minor key then modulates to its parallel or relative major key and derives from the Spanish danza dance form (Bañas, 1970). Author Raymundo Bañas explains that the danza is the “development of the Spanish habanera or tango” (Bañas, 1970, p.75). This danza is also considered the tempo di kundiman. The harana, though starts off in a minor key as well, but does not follow the triple meter but in duple meter instead. Aguilar explains that the kundiman often follows the “the subject matter around being heartbroken” (Aguilar, 2010). The same broken-hearted theme ties to the oppression Filipinos experienced during Spanish colonization. He describes both genres often confused because haranistas often sing kundiman songs during a harana (Aguilar, 2010). It was later that the implementation of operatic style, written accompaniment for piano, that made the kundiman suffice to be called an art song.

Nicanor Abelardo’s Role in the Kundiman Genre: “Nasaan Ka Irog?”

“Nasaan Ka Irog?” (Where are you my beloved?), is known to be Nicanor Abelardo’s “immortal piece” and was composed in 1923. The lyrics were written by by Narcisco S. Asistio. It is about “an unfortunate man an ill-starred love affair” (Epistola, 1996, p. 48). In 1937, a movie was released based on this song. Though not a nationalistic song like “Ano Kaya ang Kapalaran” by Santiago, this love song follows the general formula of the kundiman.

Nicanor Abelardo was born in Bulacan in 1837. He was known as a child prodigy by the age of 5 and followed his father’s footsteps as a haranista and bandurria player and even learned to play the violin (Epistola). Like Santiago, Abelardo continued his studies in Chicago Musical College. Though he created large-scaled works, his focus was on the kundiman.

A Kundiman of Kumintang Inspiration: “Mutya Ng Pasig” by Nicanor Abelardo

Nicanor Abelardo b. 1893-d.1934

Another kundiman I will be performing today by Abelardo is called “Mutya ng Pasig”, which is of the kumintang influence. This kundiman’s musical elements are suspected to have roots from the kumintang . The kumintang is an ancient genre that originated in the Tagalog-speaking region of the Philippines. This rhythmic pattern follows the rhythm of the Tagalog language. This rhythmic pattern could also be mistaken for the style of the tagulaylay, which Bañas describes as a monotonous melody sung in a recitative manner (Bañas, 1970). The opening line of Nicanor Abelardo’s “Mutya Ng Pasig” (Image 1) is a perfect example of this recitative style where the accents fall on the third beat of the first bar and second on the second bar (Santos, 2005).

Pasig River before Spanish industrialization.

This song is based on the Pasig River, the main transport route during the Spanish colonization. Many do not know this, but three tribal kingdoms thrived and existed along the Pasig: the Tondo, Maynila, and Namayan. Their lives depended on that river and was their source of wealth. When the Spanish arrived, they built the Intramuros around the Pasig and pollution caused the amount of fish in the river to decrease. “Mutya Ng Pasig” which translates to “The Nymph of Pasig”, is a song about the river nymph and the loss she experiences.

This piece is separated into three sections: “the scenic description (recitative-like); Description of the Mutya; and the Song of the Mutya” (Santos, 2005, p. 14). Abelardo also includes some text-painting in the piano/violin solos. The syncopation imitates the waters running down a river, and the chromatic contrapuntal lines creates the mysterious aura of the magical nymph (Santos, 2005).

“Sa Kabukiran” and Ignorance of the Kundiman genre

“Sa Kabukiran” is probably the most popular kundiman that most Filipinos know of. There is much work to be done. Finding these pieces are hard to find. But in its rare aspect, these songs are absolute gems. To musicians, these pieces would be a unique addition to your repertoire. Your performances of the kundiman could spread awareness of the genre. To vocal teachers, these pieces are advanced enough to challenge your students yet the language, is simple enough to learn as it is quite close to learning Italian diction. “Sa Kabukiran” was published and composed by Manuel P. Velez in 1941. It is influenced by the balitaw, much like “Pamaypay Ng Maynila”, but is set in the Tagalog and Visayan language. There are repeats signs to this, so a singer may choose to sing in the Visayan language (Image 3). A movie based on this song was released in 1947 and was popularized by the famous soprano, Sylvia La Torre. The singer of this piece reminisces the kabukiran, the “countryside”. She talks about her love of the nature around her and even imitates the bird’s singing, depicted by the piano. I believe this piece is a perfect representation of the simple and humble Filipino lifestyle in the countryside.

References

Anderson, Quiliano N. (2015, August). Kundiman love songs from the Philippines: their development from folksong to art song and an examination of representative repertoire. DMA (Doctoral of Musical Arts) thesis, University of Iowa.

Bañas y Castillo, Raymundo. (1970). Pilipino music and theatre. Quezon City: Manlapaz Pub. Co.

Barulich, F., & Fairley, J. (2001, January 01). Habanera. Grove Music Online. Ed. Retrieved 29 Apr. 2019, from http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com.librarylink.uncc.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000012116.

Castro, C., & Castro, C. (2011). Musical renderings of the Philippine nation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dioquino, Corazon C. (1982). Musicology in the Philippines. Acta Musicologica, Vol. 54, Fasc. ½ (Jan - Dec., 1982), pp. 124-147. Retrieved January 22, 201, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/932360

Epistola, Ernesto V. (1996). Nicanor Abelardo, the man and the artist: a biography. Manila, Philippines: Rex Book Store Publisher.

Filipinas Heritage Library Web site. (2018). Retrieved April 20, 2019, from https://www.filipinaslibrary.org.ph/biblio/36552/

Hesketh, J. G. (2014). Serenata. In I. Stavans (Ed)., Latin music: musicians, genres, and themes. Westport, CT: Greenwood. Retrieved from https://go.openathens.net/redirector/uncc.edu?

Kundiman at iba pa: a compilation of Kundiman pieces, Filipino classical love songs and songs promoting positive values (1994). Manila, Philippines: Likhawit Enterprises.

Miller, T. E., & Williams, S. (Eds.). (1998). Art Music of the Philippines in the Twentieth Century. In Garland Encyclopedia of World Music Volume 4 - Southeast Asia (pp. 890-905). Routledge (Publisher). Retrieved from Alexander Street database.

Miller, T. E., & Williams, S. (Eds.). (1998). The Lowland Christian Philippines. In Garland Encyclopedia of World Music Volume 4 - Southeast Asia (pp. 861-889). Routledge (Publisher). Retrieved from Alexander Street database.

Santos, Ramon Pagayos. (2005). Tunugan: Four Essays on Filipino music. Diliman, Quezon City: The University of the Philippines Press.

Talbot, M. (2001, January 01). Serenata. Grove Music Online. Ed. Retrieved 29 Apr. 2019, from http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com.librarylink.uncc.edu/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-0000025455.